An American in Cuba: Part One

This is part one of a two-part series on our fellow traveler Justin’s visit to Cuba. Click here for part two.

In 2009, few Americans could visit the island of Cuba and get away with it. Most who would visit worked full-time as journalists, or kept a pretty good secret about how they bravely traveled via Mexico, believing Cuban immigration would not stamp their passport when they entered. Neither option worked for me. However, I did manage to get a license from the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control, which allowed me to spend money in the communist state. It was understood that I would not spend more than $125 per day, I would stick to the plan I gave them — taking pictures and interviewing normal Cubans — and otherwise act as a freelance journalist. So, over Thanksgiving of that year, I took a charter flight from Miami and spent five days in Havana.

Why? My curiosity with communism was growing more intense through 2008 and 2009. During that time I was regularly reading news from North Korea and China, travel stories from Vietnam, and browsing beautiful photographs from Cuba. Curiosity, combined with affection for photography, was what brought me to Cuba. Plus of course it was forbidden fruit.

Why? My curiosity with communism was growing more intense through 2008 and 2009. During that time I was regularly reading news from North Korea and China, travel stories from Vietnam, and browsing beautiful photographs from Cuba. Curiosity, combined with affection for photography, was what brought me to Cuba. Plus of course it was forbidden fruit.

What did I expect of Cuba? I learned a fair amount before visiting: their politics, their history, and various statistics about health, education, and the economy. It all led me to believe Cuba was better off than many Latin American countries: a higher rate of literacy, longer life expectancy, higher “Human Development” (HDI), and much lower unemployment. Basically, I figured, communism had made the country poorer, but it satisfied every basic human need. It didn’t take long in Cuba to realize how badly I was misled.

Before the trip, I struggled to find just two Habañeros on the internet who might be able to host a visitor. The tricky part is that Cubans are not allowed to house foreigners without special permission. They were noncommittal but very polite, and I agreed to meet a girl named Lisa at her home in Centro Habana, just a block from the Malecón and the Gulf of Mexico. When I arrived, Lisa was working at her day job. Her mother walked me a couple of blocks south to Calle Animas where I would be staying.

The casa particular was just fine, and the woman who owned it, despite speaking perhaps four English words in five days, managed to take care of me quite well. Breakfast at her house every morning was certainly the most reliably satisfying meal I would get each day. Bread, butter, fruit, and an egg. I remember the sound the egg made in her frying pan. She always used a lot of manteca and had the gas on high. She was intent on cooking that egg in less than 20 seconds, grease burns notwithstanding.

Eating in Cuba is far from exciting and it can be downright disgusting, Almost everybody is using the same fairly stale ingredients. The bread at breakfast tasted suspiciously like the bread in two different Cubano sandwiches from the street, and just like the bread served at a state-run restaurant in Old Havana. I found pizza being sold around the city — always a favorite — but it looked the exact same no matter who was selling it. There seems to be one supplier for any given item.

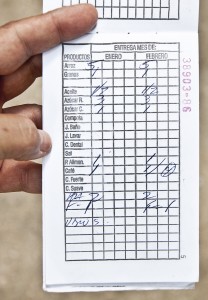

The main reason, of course, is that the economy is state-run. All major industries, including agriculture and food production, are managed by the state. Cubans also keep ration cards that specify and strictly limit the food they will receive. Any money they make from their jobs is virtually worthless, so it is extremely difficult to afford foreign products. Wages are pathetically low, besides. There is an expression in Cuba: “They pretend to pay us, while we pretend to work.”

But the first and most lasting impression from Cuba is not the taste, it is the image. Seeing Havana with my own eyes was the top reason for going. You can find pictures of the crumbling buildings all over the internet, but firsthand sight of the situation is shocking. At any sensible or humane standard of risk, most homes in Habana Vieja and Centro Habana would be condemned for human habitation. They collapse on a regular basis. Who lives in these houses? My understanding is that Cubans are not allowed to buy or sell real estate freely, so I would guess that families (extended or otherwise) have been living in houses for about 50 years. If a family leaves/escapes or dies off, you can bet that squatters will take up long-term residence. Some houses are completely hopeless. The picture above is of a tree growing from within a house, just two blocks from the Paseo del Prado, and its branches are coming out of the third floor windows.

But the first and most lasting impression from Cuba is not the taste, it is the image. Seeing Havana with my own eyes was the top reason for going. You can find pictures of the crumbling buildings all over the internet, but firsthand sight of the situation is shocking. At any sensible or humane standard of risk, most homes in Habana Vieja and Centro Habana would be condemned for human habitation. They collapse on a regular basis. Who lives in these houses? My understanding is that Cubans are not allowed to buy or sell real estate freely, so I would guess that families (extended or otherwise) have been living in houses for about 50 years. If a family leaves/escapes or dies off, you can bet that squatters will take up long-term residence. Some houses are completely hopeless. The picture above is of a tree growing from within a house, just two blocks from the Paseo del Prado, and its branches are coming out of the third floor windows.

Most of my time was spent walking around Havana. One day I got to explore southern Havana. Starting from the house I walked southwest to the bus station to inquire about trips to Trinidad, then turned east through a rather unfriendly part of Havana. The dodgy areas usually seemed less Spanish, more Russian in appearance. My walk east took me past an old, seemingly useless and abandoned train station. It took a while to get past it, but when I did, a train rolled over me on elevated rails.  Apparently it’s still in use! In my mind, something about a train station with no people or activity nearby seemed strange, and I conceded I was lost. Eventually I wandered through the southern part of Habana Vieja and found a neighborhood with actual charm. Happy people, young and old, black and white, were passing the time around their homes and for the first time I was attracting little attention. To keep it that way I took a few quick pictures and moved on. Also it was getting late, and when the sun goes down, it is risky being a foreigner with an expensive camera. Theft is common, as police reminded me on a few occasions. This was not surprising because many of Havana’s busiest streets are not lit. If you can make out the faces, you will see looks that say “you must have taken a wrong turn.”

Apparently it’s still in use! In my mind, something about a train station with no people or activity nearby seemed strange, and I conceded I was lost. Eventually I wandered through the southern part of Habana Vieja and found a neighborhood with actual charm. Happy people, young and old, black and white, were passing the time around their homes and for the first time I was attracting little attention. To keep it that way I took a few quick pictures and moved on. Also it was getting late, and when the sun goes down, it is risky being a foreigner with an expensive camera. Theft is common, as police reminded me on a few occasions. This was not surprising because many of Havana’s busiest streets are not lit. If you can make out the faces, you will see looks that say “you must have taken a wrong turn.”

Walking, eating, and taking pictures is a terrific experience, but the greatest privilege of all was talking with actual Cubans. Meeting Lisa, I was impressed. Before I met her, I met her family and saw the home where they lived. Her family’s home was a little smaller than most, modestly decorated, but nice and basically normal. Lisa had a job at the Russian embassy, where she spoke Spanish, English and Russian regularly. One day that week she accompanied Russian visitors and embassy employees to enjoy some time on the beach. Nice gig. She was rare among Cubans at the time because she had her own cell phone, plus internet access at work. I learned she had just turned twenty-seven.

One day Lisa and I walked through most of the Vedado neighborhood in the western part of the city. It was nice by Havana’s standards. There were large, well-kept homes, grass and sidewalks. It seems that most of the popular casas particulares for foreigners are in this neighborhood. It is safer, quieter, and more likely to provide electricity and hot water but it does not look like the Havana we usually see in pictures. We passed a few nice looking restaurants, an ice cream shop, and a movie theater so overflowing with patrons, they sold tickets to sit outside and watch the movie on a 24” television. On the way to Vedado, we walked along the seashore and passed the U.S. Interests Section (of the Swiss Embassy). It is a small fortress on the Malecón. Prime real estate. It has an electronic sign on the roof. It was not lit when I was there, but Lisa explained that at times messages have been displayed on the sign, usually in reference to human rights issues in Cuba, such as political imprisonment. “Basically, messages that say ‘you are not free’,” were her words. The sign, the tough security guards and the high walls must have been attracting attention, because the Cuban government felt it was necessary to erect an “anti-imperialism” plaza nearby with a statue of Cuban independence hero José Martí. He holds a child in his arms and damns us with a pointed finger.

Photo source: havanatimes.org

Regardless of whether you were American, or any tourist in Cuba, Havana was a tense place. People mostly seemed frustrated at how low their country had fallen. One day I was chatting with a stranger, and after a few minutes he asked me to try “this great place” for lunch. While we ate and watched the waiters pretend to work, he showed me his ration book. It is basically a checklist of items to be doled out each week. Talking about it, he seemed angry, scared, and a little embarrassed. The ration book had been around for 50 years in Cuba, so its existence was not the issue. He was losing faith that the government could even provide small quantities of food. His feeling was justified. In the next year, about a half million Cubans were kicked off the public payroll, and Fidel himself said “the Cuban model doesn’t even work for us anymore.” Basically, Cuba had hit rock bottom, and something needed to be done.

Pingback: This World Rocks An American in Cuba: Part Two | This World Rocks

Pingback: This World Rocks | Landing in Myanmar: First Impressions | This World Rocks |

Pingback: Seyahatte Çekilmiş İnanılmaz 27 Fotoğraf | OdaNesi ?!|OdaNesi?