Uncovering Burma’s WWII Past – Part One

“You’re not the Forgotten Army…

Nobody’s ever heard of you.”

Towards the end of 1943, the British/Indian Army in Burma(Myanmar now) was in pretty rough spirits. Nearly two years had passed since the Japanese had invaded Burma, and the Allies were suffering one setback after another in their attempt to regain control of the country. Repeated counter-attacks by both the British and Indian armies failed with heavy casualties. Parts of the country that the British ignored because they believed to be “impassable jungle” had been infiltrated by the Japanese, causing the British to be forced to retreat all the way back into India.

As bad as the situation was, the morale of the troops suffered the most from the constant belief that the world had forgotten about the Burma Campaign. When Lord Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander in SE Asia, came to Burma in the Winter of ’43 to increase troop morale, he decided to use this belief of being forgotten as a motivator. As he spoke to groups of troops throughout his visit, he repeated this quote over and over again:

“You’re not the Forgotten Army on the Forgotten Front. No, make no mistake about it. Nobody’s ever heard of you.”

Visiting Myanmar’s WWII Sites

Tracking down WWII sites in Myanmar is not easy. There are a lot of things going against me here that make it difficult:

1. There are no reliable guides or guidebooks on where to go or how to get there.

2. With very few exceptions, there are no markers or memorials to help find historically significant locations.

3. Most of the heavy fighting was done in the far north, sometimes even into India. Most of the locations are still off limits to visitors and crossing to and from the India/Myanmar border by land is not allowed by either country.

4. Years of neglect and civil unrest have left little actual sites to see.

So that’s what I’m up against. I’m going to start in Bago (formerly Pegu) and walk in the 1942 footsteps of the Japanese Army.

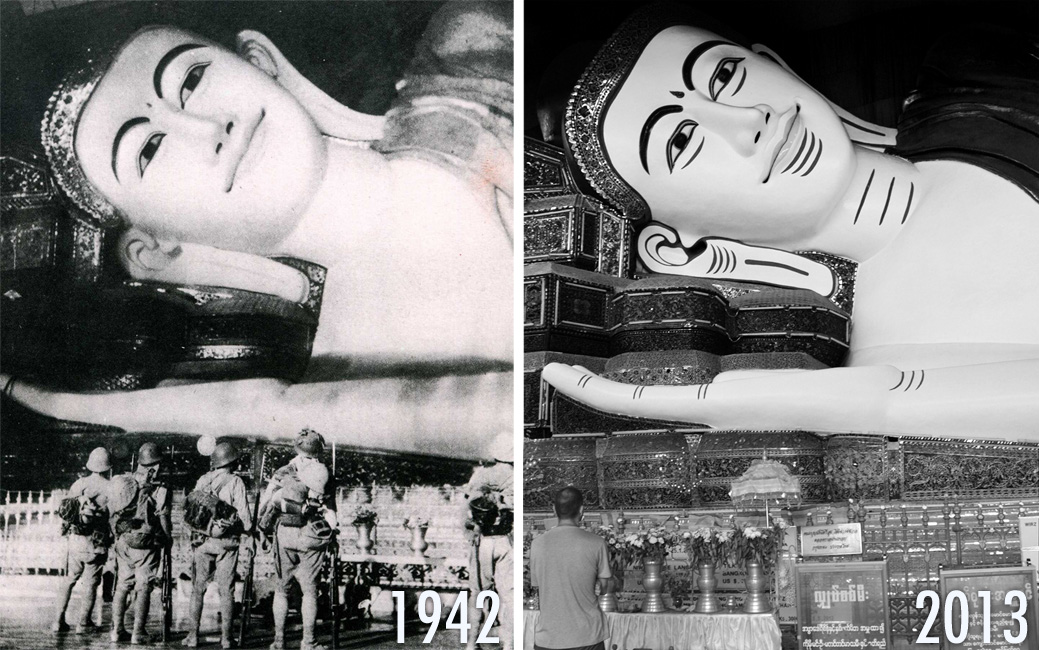

Bago was the last city the Japanese Army went through before it reached Yangon (Rangoon). I stopped by the Shwethar Lyaung Pagoda (pictured above) to see if the famous reclining buddha still looks the way it did when the Japanese reached it in 1942. The only other site to visit around Bago is the Taukkyan War Cemetery about an hour south of the city. It’s a British cemetery containing the remains of 6,000 soldiers from the war. Sadly, we weren’t able to make it there on this visit. Instead, we’re heading east to Sittang, site of one of biggest military disasters in British history.

The Beginning of the End of the British Empire: The Sittang Bridge Disaster

Background

February 22, 1942. It had been 75 days since Pearl Harbor, and the Japanese had not showed any signs of slowing down. They had successfully invaded Singapore and Malaysia, made their way through Thailand and into Southeast Burma. Still 50 days away from America’s first offensive action on Japan (The D0olittle Raid), the British had found themselves in a desperate situation. Stop the Japanese from taking Burma (a British colony at the time), and protect aruegably the most important British colony, India.

After losing battles at the Burma/Thai border, the British/Indian Army found themselves quickly retreating westwards towards the Sittang River. There they had to cross a narrow rail bridge that could barely handle one-way traffic. This bridge, the Sittang Bridge was the last major obstacle between the Japanese Army and its objective of occupying Rangoon. If the British lost this bridge, not only would Japan have an easy march on Rangoon, but the British would also be cut off from China and forced to retreat into India, leaving Burma in the hands of Japan.

The British set up defenses on the east bank of the river and nearby hill to prepare for the Japanese attack. The bridge was also rigged with dynamite so that they could blow the bridge in the event that the Japanese broke through the defense lines. They could not risk the Japanese capturing the bridge in tact.

Pagoda Hill

The main stronghold on the east side of the river was on the high ground known as Pagoda Hill. Starting at about 1am on February 22nd, the hill and its surrounding area saw a complete 24-hour span of brutal hand-to-hand fighting. There are no known photographs of the battle or the aftermath. The only known visual from that day is the famous painting by military artist David Rowlands:

David Rowlands’s painting of the Battle of Sittang Bridge. Painting depicts the fighting on the river’s east bank as viewed from Pagoda Hill.

Visiting Pagoda Hill today is a quiet, rarely visited religious site, complete with a small active monastery. The original pagoda is still here, but you can’t see it as they’ve built a new one directly over the top of it. One of the higher points on the hill is an old cement stupa that I presume was used as both a look-out point and guard.

Disaster Strikes

At 5am, nearly 30 hours of continuos fighting had caused complete confusion on the the west side of the river bank. The British Commander, John Smyth, was unaware that the Indian Army was still successfully holding the Japanese from taking Pagoda Hill, and assumed that the majority of the army had made a successful retreat to the west bank. At 5:30 am, in fear of the Japanese taking the bridge, Smyth made the call to blow the bridge, stranding more than 6,000 soldiers on the other side.

The Sittang Battlefield as it looks today. The pillars from the original bridge are still standing. The land along the river was the scene of immense suffering of the wounded who were unable to swim across to safety.

After five minutes of complete silence, chaos began again. The rest of the day consisted of Indian troops trying to find a way to cross the mile-wide river any way they could while a select group of heroic troops continued to fight off the Japanese. The stranded troops who knew how to swim got across, but had a difficult time finding boats because most had been destroyed before the battle. Many built make-shift rafts and other floatation devices to help get across. The 30+ hour battle had left hundreds of wounded men on the wrong side of the bridge, and the British were lucky that the Japanese chose not to completely annihilate the remaining soldiers. The Japanese were more interested in crossing the river, than slaughtering the remaining troops and began moving north to find a narrower place to ferry across.

After the bridge was blown, hundreds of wounded soldiers had to helplessly wait on the riverbank for help to come.

Aftermath

The battle was a decisive Japanese victory, and it marked the beginning of the Japanese occupation of Burma. The British/Indian Army in Burma was left in disarray, and had lost a considerable amount of supplies on the other side of the bridge. They retreated all the way into India, where they would remain until finally being able to re-enter Burma for a counter-offensive campaign with the Americans and Chinese. Burma would finally be secured and liberated from the Japanese in July of 1945, when ironically the British finished off the Japanese back where it all started, at the Sittang River.

Japanese occupation of Burma was the breaking point for the British Empire. Once was the war was over, the Burmese had no interest in every being ruled by the British again. Although India had never been reached by the Japanese army, the people there had lost their trust for the British, who were no longer an invincible regime. Within three years, both Burma and India would be independent. Because the Battle of Sittang Bridge was the decisive event leading to Japan’s invasion of Burma, the Disaster at the Sittang is considered to be the defining moment in the decline and fall of the British Empire.